Emerald Exhibitions- Owner of Surf Expo, Outdoor Retailer, Interbike and Others- Going Public. Why?

Last Week Emerald Exhibition (EE) filed the S-1 that includes the first draft of its prospectus to go public. Because it’s the first draft a lot of information (like price per share and number to be sold) is missing. Still, it’s worth a review. We’ll summarize the company’s history and activities, look at the financial results, talk about their market and how they see themselves competing, and discuss why they are going public. I also want to point out a risk factor they seem to ignore.

Who’s Emerald Exhibitions?

What is now called EE was acquired from The Nielsen Company by Onex in 2013.

“Onex is one of the oldest and most successful private equity firms in North America. Through its Onex Partners and ONCAP private equity funds, Onex acquires and builds high-quality businesses in partnership with talented management teams.”

In January 2014, EE bought George Little Management for $335 million. It operated 20 trade shows. Since then, EE has made 12 other acquisitions. They expect to make more and you’ll see how that relates to the initial public offering (IPO) when we get to the financial situation.

Right now, then, EE “…operate more than 50 trade shows, including 31 of the top 250 trade shows in the country as ranked by TSNN, as well as numerous other events.”

Of their 2016 revenue of $324 million, $71 million came from what they characterize as “sports.” They’ve got 18 shows in total in the sports category. The largest category, at $124 million, was gift, home and general merchandise. Here’s how they describe their sports shows.

“Exhibitors…are manufacturers or distributors of equipment, gear and other goods serving these markets, while attendees are typically retailers or wholesalers who purchase these goods for resale. These shows also have a many-to-many environment where thousands of specialty sports retailers interact with hundreds of specialty equipment and athletic apparel manufacturers. The Sports shows target the highly fragmented sports retail market where sports enthusiast clientele are typically served by independent specialized retailers. Attendees and exhibitors in this market tend to be primarily focused on high end, performance-oriented, experiential products, where minor improvements in performance are a differentiator. Given these characteristics, it is important for attendees to test and learn about the products in person to be able to sell them to their customers, which makes this market ideally suited for trade shows.”

They talk about “Self-Reinforcing Network Effects” in the trade show industry. They put it more tactfully than I’m about to put it, but their basic concept is that people have to attend. They note, I guess as a result, that they’ve had “a demonstrated capacity to achieve regular annual price increases across our portfolio.” It’s one of the things they say make their business model attractive. Here’s how they put it.

“Effective trade shows are characterized by a self-reinforcing business model, in which attendees with authority to make purchasing decisions make trade shows “must-attend” events for key industry suppliers. High-quality exhibitors, in turn, introduce new products and innovations and set trends, thereby driving increased attendance. This self-reinforcing “network effect” helps solidify a trade show’s leading position for the long term and establishes significant competitive advantages. The value of a trade show to an exhibitor is a function of the quality and quantity of the attendee base. The quality of attendees can be measured by the extent to which attendees have the authority to make purchasing decisions, as well as by the amount of purchasing that occurs during or after a show. According to Exhibit Surveys Trade Show Benchmarks and Trends, approximately 82% of trade show attendees in 2015 (the last full year for which such data is available) held some purchasing decision-making power in their respective organizations, while approximately 51% of trade show attendees planned to make purchases during or following shows.”

I don’t have any perspective on their jewelry or technology shows. Certainly the sports/active outdoor markets we’re interested in are experiencing some trends that EE seems to ignore.

The decline in the number of retailers and closing of stores would be the first one. Next would be consolidation, where we end up with fewer but larger brands and retailers. What I think I see at our trade shows includes:

- Fewer people staying for less time

- Generally smaller booths, means less booth revenue

- There are fewer retailers to show up- especially among the independent specialized retailers

- Less actual buying going on at the shows. Did you notice the statistics in the above quote? 51% of attendees plan to make purchases during or following the shows? Bet that’s way down from eight or ten years ago. And did they make those purchases because they went to the show?

- More and more retailers and brands are meeting and making purchase decisions outside of shows. The internet has made it easier to perform some trade show functions.

If you agree with my points, then it will have been hard for you to read the EE quotes above without wondering, as I did, how they address these issues. They kind of show up in the risk factors.

Maybe they don’t impact their specific shows even as they impact active outdoor shows overall. EE would also point to their “highly attractive business model” as a strength despite these trends, and that makes some sense.

With just 2% of a U.S. trade show market EE estimates at $13.5 billion, EE believes it is the largest player in a highly fragmented market ripe for some consolidation. They also note their diversification, efficient cost structure, a model that doesn’t require much in the way of capital expenditures, and a front-loaded cash flow based on customer deposits as strengths.

If they can help industry consolidation along with continued acquisitions and apply their strengths to a larger revenue base, the issues I listed don’t go away, but they will surely have more impact on EE’s smaller and less diversified competitors.

That’s a valid thesis, and I’m a bit surprised they don’t say it more directly. But even if they are correct, it’s fair to ask if the traditional trade show model will endure and prosper given the internet, automation, and an at least dramatically shortened timeline for the design, production and delivery of certain kinds of products. I suppose that even if the trade show model changes dramatically (EE seems to be betting it won’t) it will still be advantageous to be the biggest player.

Financial Results

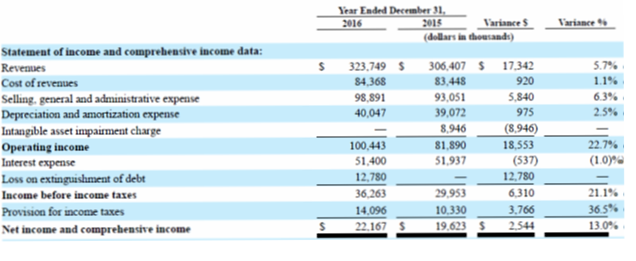

Below is the summary income statement for EE for the years ended December 31, 2016 and 2015 along with the variances between years.

You’ll note that they had an $8.9 million asset impairment charge in 2015 and a $12.78 million loss from paying off some debt in 2016. You might want to mentally take those into account as you review the operating and net income lines.

More importantly, I want you to check out the interest expense line. It’s north of $51 million in both years; more than twice the company’s net income. Reducing that wouldn’t be a bad way to improve the bottom line.

The first time I saw the balance sheet, I almost keeled over- it shows a current ratio of around 0.5. That’s supposed to be something you can’t operate with. Then I realized that they carry the deposits they receive from exhibitors prior to their shows as deferred revenue, a current liability. That number is $172 million at the end of 2016, and explains why the current ratio, at first glance, looks unsustainable. But it’s not actually a problem.

Meanwhile, we’ve got total equity of $528 million. Due to all the acquisitions, goodwill and intangible assets are the end of 2016 were $930 and $541 million respectively. That’s okay if those asset values hold up. There’s no inventory on this balance sheet. Always nice to not worry about that.

Finally, we’ve got $710 million in long term debt including the current portion. It’s all due within five years, with most ($687 million) due in years three to five.

Why Go Public?

First, they want to pay off some of that debt. “Reduce our financial leverage” as the Use of Proceeds section says. We don’t know how much they are going to pay off. This early draft has a blank place where that number will go. But they may incur some more debt, we learn, as they pursue acquisitions.

“Despite our current debt levels, we may incur substantially more indebtedness, which could further exacerbate the risks associated with our substantial leverage.” The other reason to pay off debt, of course, is that interest rates seem to be moving up and, as highlighted above, they are paying quite enough interest already.

You might want to look at your own investments and think about what happened to their income statements if they are leveraged and rates move up a couple of points.

EE also want to “…create a public market for our common stock and enable access to the public equity markets for us and our stockholders.” Among the selling shareholders, in amounts not yet specified, will be Onex and various officers and directors. Good for them. Everybody likes a payday.

Even after Onex sells a yet unknown number of shares, it will still “…have the ability to control the outcome of matters submitted to our stockholders for approval, including the election of our directors and the approval of any change in control transaction.” Onex will also be the largest beneficiary of a quarterly cash dividend the company expects to pay. Their existing leverage and plans for further acquisitions might make it a good time not to pay a dividend, but that’s completely up to Onex.

EE will come public as what’s called an Emerging Growth Company. That means they will be subject to less rigorous reporting and other regulatory requirements than other public companies. You can see what those reduced requirements are on page 14 of the S-1.

I’ll be really interested in seeing just how much money they expect to raise. In spite of their plans to get more exhibitors and sell more square feet, EE’s revenue growth in 2016 from its existing shows was just 2.6% (3.5% less 0.9% due to some discontinued events). The rest came from acquisitions.

While they expect to raise more debt, presumably for additional acquisitions, they are no doubt planning to use their public stock as an acquisition currency if all goes well. Consolidating a fragmented industry is a common way of building a company. Ask the funeral homes, garbage collectors and, more recently in our back yard, the winter resorts.

But I keep going back to EE apparently ignoring some of the trends I see in the trade show world I know. Those trends might partly explain why organic growth was only 2.6%. There are going to be some surprises for all of us as trade shows evolve.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!